top of page

essays | places

India

feel everything

Yes, you can see everything, taste everything, smell everything, and experience everything in India, but most importantly, you can feel everything there. The human condition, raw, in all its extremes and middles and aberrations cannot not touch you one way or the other. The colors cannot not dye you a little. The turmoil cannot not whirl you past dizziness. The cement, the jungle, the desert – everything is sweating life’s essence until it drips from the walls and cheeks and runs to the Ganges or the gutter. There is nothing before or after India; it is the moment zero in the flesh, a permanent reincarnation of the origin molecule, inflation and collapse happening at the same time and in the same direction.

Some things were old, some things were gold, some things weren’t things at all, but everything was noteworthy.

Poverty was not always as striking as its clichés. At times it was as subtle as toothbrushes pinned to a backdoor, hinting at the absence of a bathroom.

The Indian subcontinent was vast but no match for its population. Finding a place where you didn’t find a billion people was like trying to find a haystack in an ocean of needles. Social ties were musculous as tightropes, friendships well done. There was certainly a certain intimacy to them, but of a more innocent nurture than a brutally open nature.

Colors were cultural. People wore them like a second skin, a rainbow skin so elastic and so far stretched from black to white that all the colors were welcome in the middle.

Everybody raved about Goa’s raves, and it was clearer than the Arabian Sea that there wouldn’t be much India there. But throw a rock and you’ll hit a peaced-out expat on a scooter. No no, seriously, try it, go ahead and throw one – they’re so chill, they won’t even know what hit them. I'd taken a nightbus down from Mumbai. The night trains were great, but the night buses greater if you liked the added privacy of your own berth tucked away behind a curtain, and the potential added intimacy of a stranger being booked into that bed with you.

places / stories

Delhi / Juggling Juxtapositions

My first distinct memory of India is a cliché cow, walking into a train station with human confidence and swagger to take a significant dump in the sultry waiting hall before lying down and calling it a holy day. Right the next memory is Delhi’s mega-modern metro that served the route between the capital and the future – bright, AC-chilled, progressive signs pointing out seats for differently abled people, not “The Disabled.” What more is there to say? India is big on juggling juxtapositions. You could throw it a ball, a burning knife, a cow, and a parallel universe, and it would just keep going.

Rajasthan / Fairy Functions

To reach Rajasthan, you had to take a night train, step off in the morning, trip, and fall into that tale. The desert state was pure fairy dust, or maybe just dust, but at least that’s real, and what’s the difference really? Was that an elephant at the traffic light just now? Udaipur, Jaipur, Jodhpur, the Rs rolling like purrs – those city names sounded exactly what the wave functions of their alleyways looked like.

Architectural time travel was easy and cheap. All you had to pack were your feet and eyes, and you were fully equipped for a trip through the centuries, no matter where you stepped or looked. They had built beautifully and significantly back then – so much so that those swimming places and whatnots stood the test of time and taste. Of course, none of them were built for the many, but none were ever anywhere. The many had their little things, like little flowerpots on little roofs of little houses in little alleyways. Fortunately and affordably, such cozy vibes have always been home to me. And while the appeal of grandeur is not fully lost on my eyes, my butt cringes at the idea of sitting in those palatial halls surrounded by little more than emptiness.

It was a place that wore the past like it never went out of style. And with all those riches shining across the centuries, the poor looked even poorer. Poorest really.

One night – I think it was in Pushkar or maybe Udaipur – I almost died a silly death – death by cow – almost as silly and preposterous as using four em-dashes in one sentence. There was a celebration and lots of people clogged the streets. Maybe there were lots of cows too, but I only remember the one with its horns painted red, looking like the devil in his most ridiculous disguise, pushing towards us, and then, right next to me, yanking its head towards my chest and missing me by a split-hair's breadth. One word of advice, should you ever be in that situation: don't flinch and if the cow gets you, you'll be the life of the party in the afterlife with that story.

After I didn't die, I probably had another one of those Palak Paneers, threateningly green like deep sea algae. A few dahls and curries later we were off to Agra.

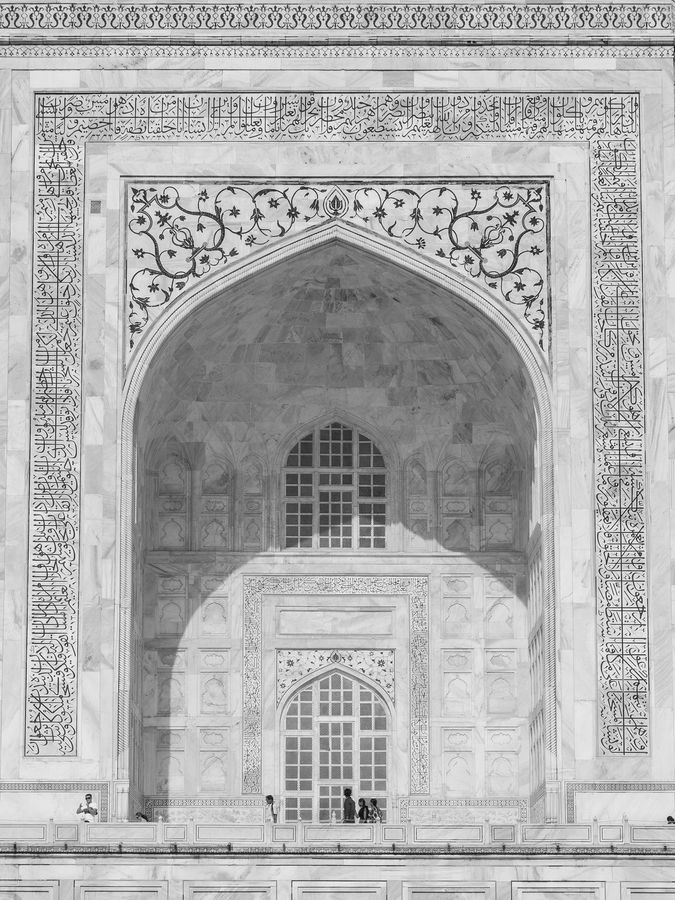

Agra / The Density of Love

White marble, the complexion of light, for her, for love. Taj Mahal. Makes you wonder about the density of love – if love is burying your third wife out of six after she died in childbirth with kid number 14. Taj Mahal. Not all that romantic maybe. But Agra had more than a marble heart. When you looked at its fabric from up close, you saw right down to the rumbling guts and a little past those you saw a crazed soul that was always busy.

Mumbai / The Melody, Louder

I’ve been to Mumbai, and I’ve been back to Mumbai, and I’ll be back again, but I need to stop brushing it and start running my fingers deep through that thick mane, because I know it’s a harp with many million strings, and I want to hear the melody, loud and louder, until well after I cut my fingers.

She picked me up at the train station with her neither-here-nor-there-neither-sari-nor-blouse long white top swaying in the wind like a cape, like it was causing the wind, and her black mane fluttering just a little calmer. And then a few days later she cut it with the determination of change, a full donation worth of thick hair, a walking thunderbolt striking me down in the middle of the mall. At night, we would take a stroll along the podium. The skyscraper patio of the upper middle class.

Kerala / Mountain Tea and Brackish Sea

Kerala

mountain tea

brackish sea

twister road

houseboat

a mix of tricks

a flavor a little different.

Our houseboat – and I assume every Keralan houseboat – had that moldy smell, like being inside a well. You wouldn’t quite notice it much after a few breaths. And either way, the only reason to ever set foot below decks was sleep, and when you sleep, well you sleep.

That time we went for a swim, only two of us saw the sea snake wriggling by, and where our eyes met, there was little ambiguity: we wouldn’t weigh the others down with that unnecessary knowledge. You don’t wanna weigh people down in the water. Dinner that night wasn’t any less creepy. Our captain offered the catch of the day for those who wanted a little non-veg extra: an underwater dungeon creature that was so mutantly distant in resemblance to a langoustine that he might as well have fished it out of some gas ocean on Jupiter. And it tasted the part too. And it wasn't cheap either.

Tamil Nadu / Two Mini-Lives

Chennai was a smoothie of cement and trees that Lord Rama and his monkey army had poured out by the beach. And all that stuck to you and grew on you until you were all covered in it without any desire to wash it off. Two fine mini-lives I’ve lived there, a few years apart, setting an interval for future returns.

The first time around, I lived right on Anna Salai near the botanical garden. The place had terrible reviews, but I wouldn’t say that they were terribly deserved. It was what it was: cheap. My room was blue and she wasn’t allowed in. I found out the loud way when desperate knocks started hitting the door like missiles. All scandalized, both the receptionists/managers/owners had scurried up the stairs to protest the violation, which was more of a moral than a house-rule-ish kind. Since it wasn’t written anywhere, I guess it went without saying, culturally. To my surprise, their moral antibodies kept them completely immune to the innocence and decency she radiates like no other woman I know.

There was no kitchen, but fortunately India is one of those blissful places where eating out can be cheaper than lifting your own spatula. My staples were omelets and pakoras, which I would pick up in the mornings and evenings in a charming, grimy back alley around the corner. In the mornings I would pick up some more after I became something like friends with an old homeless couple that lived along my way to work. Our only lingua franca was smiles, but they said it all. Only after a few months, when I visited them with an interpreter as part of the project I was working on, did I get a chance to talk to them. Turned out they were Christians and that they saw me as heaven-sent, when all I was, was back-alley-sent. We were trying to build a food network for the homeless, who turned out to be some of the happiest people I’ve come across as long as they weren’t homeless alone. And alone they weren’t usually. And usually they lived on the street with their entire family, eager to send their kids to school and put food on the cardboard table. I liked them and loved how their laundry would color the sterile fences of high rises like the LBR Towers.

That apartment we shared the second time around was a third-floor basement, but not not cozy. The cheap dosa restaurant right outside was a fat perk. Dosa dosa dosa, can’t ever have too many dosas. My wallet still looked pretty anorexic in those days but just nourished enough to have an appletini at Amelie’s now and then.

Strolls along Marina Beach didn’t hurt at all, unless you’d step onto all the trash. But to me, the way there was the true journey-is-the-destination-bla-bla tale, for no road in Chennai gets me more than Cathedral Road and its wordier extension Dr Radha Krishnan Salai, leading from that little botanical garden all the way down to the beach. That road is a shelf and every building a book, and every book a genre. If you walk slow enough, you get to read enough to decipher a meaning of life or two. I mean, don’t get me wrong – when I’m in Chennai, I love me a good White’s Road too – passing by the Wild Garden Café’s wild garden café and whatnot – and you can’t go wrong with or on Anna Salai Road, but to me, Cathedral Road is the most spiritual experience. And I was never attacked by a caterpillar there, and neither by a motorcycle – both asterisks I have to attach to White’s road – so that’s a plus. Of course, being run over by that motorcycle was my fault entirely and I accept the scar gladly, for a lack of other choices – it is just what happens that one time you don't focus a million percent while crossing a street in India with that killer traffic. But that caterpillar was no accident and had been waiting for me right outside the Wild Garden Café’s wild garden café, and I blame that black beast for every single seta she had to pull out of my neck that night. “Am I gonna die,” I asked myself, feeling the itch along my jugular. “Probably, but maybe not,” it echoed back. Fair enough.

Not many parks in Chennai, but every street a green canyon with trees on growing sprees. The rivers were sewers. Slums like Triplicane were a reality check. The festivals an escape from reality.

Tamil is not a language. It’s a melody. Soft and round like the sea gooseberries we found in Pondicherry, and kinda like the name Pondicherry, and with a wave-like rhythm, lalala. It comes after the people who speak it, who live life so melodically. It was strange that she was a stranger there almost as much as I was – a stranger in her own country, a Mumbaikar who spoke a different language and wore a different face as though she had arrived from another planet, just not quite as far away as the planet I’d arrived from – stranger almost than this sentence that was. The differences between Indian states were less like regional flavors, and more like national idiosyncrasies. Citizens of the same land had to default to English – a linguistic import from a faraway nation. It was both logical and hard to understand that they borrowed this common denominator from their former oppressor; after all, it had been forced onto them for a long time, which seems as much reason to embrace it as it could be reason to reject it.

They embraced me too, the foreigner, with wide smiles they wrapped all around me, and coddling services that felt like professional cuddles. Given history, I would have understood racism towards white-old-me to the point of welcoming it. But no. They loved me. The radius of their love for their own people was a little narrower. Social ties were strong but short. Often they wouldn’t extend to those of another caste, those who were a shade darker. I have never understood this intranational racism – neither in India nor against indigenous people elsewhere – and fortunately, I never will.

What I will understand, always, are the physics behind the kind of human gravity that makes the world spin. Like clinging on to her like a wet t-shirt while she rode that dinky, sputtering, miniature moped back to Pondicherry after we found the sea gooseberries at Serenity Beach.

AID India was a wonderful nonprofit to work with – the right mix of smart compassion and down-to-earth grassroots proximity. One of my favorite things about going into the office was how people would go in, or rather how they wouldn't: everybody took off their shoes outside. It made the office feel a little less office-y, and so did the collegial sweetness.

Working there for the second time was no less inspiring than the first time around. Chandra's invigorating vigor, Selva’s supercharged drive, Parvathy’s lean precision. It clicked and they clicked. Human talent and accomplishments were through the roof of that office, and its walls burst with intelligent compassion, AHA-ideas, and follow-through implementations. Among the office youngsters – and I do include myself in that group, if not on paper then at the very least in spirit – friendships extended beyond the workday and sometimes long into the night, when we plotted our escape from the escape room, or danced our feet off at the club.

So long friends.

_______

elsewhere

bottom of page